PRESS

1974

Toni Bonavita: Historic Art Critic for Rome's "IL TEMPO"

(national distribution daily)

IL TEMPO

Rome-february 6 1974

Scaretti's Puzzles.

Scaretti's Puzzles.

A new gallery (Etrusco-Ludens, 77 Piazza Navona) adorns its rooms with artistic

'puzzles' created by Lorenzo Scaretti. Scaretti is an artist who proposes a playful vision of reality, punctuated with a polemic outlining his own particular philosophy of life.

Often, contemporary art has been deemed as an appropriate expression of the world, one which is viewed with new eyes, with minds free from the traditional concepts of painting and sculpture. To compare it directly with traditional art, it's been said, would be as illogical as conversing with someone who not only speaks a different language, but with whom we have no intention of understanding anyway (and vice versa).

However, within traditional painting and classic sculpture, we are able to distinguish between what's good and what's bad. Why then do we feel we have to either accept or reject the whole of performance art or pop art in one fell swoop?

Should we consider art a game? Okay. But there are idiotic games and intelligent games. The ones played by Scaretti seem so precise and finely tuned as to be games no longer, but rather the development of a thought process, a spiritual aggression which is subtle rather than shocking, which sneaks into the brain and produces a philosophical reaction, leaving its images multiplied by countless sensations, always different, always valid.

These objects at first bring to mind the Dadaism of Duchamp, of Man Ray, of certain Futurists, but they are eventually understood as connected by a personal and consistent discourse. This discourse may be argumentative but it is certainly efficacious. The theories of symbols, of ideogram characters as the origin of painting and sculpting, the link between these characters and phonetic sounds form the basis of the interest of this young artist, who is also endowed with inventiveness and a sense of humor, which at times borders on ferocious satire.

'The modern human mind,' says Scaretti,'tired of computerized logic, leaps to new revelations and intuitions through the use of puns. Words ( or phrase objects, the graphic expression of words) are important: man is judged by the words and phrases he writes and speaks, and not often enough by the images he sees in his mind's eye and then reproduces.'1)

This is to say, in simple terms, that representation basks in a freedom from consequent limits. Determining the function of a particular image leaves us free to interpret it or not, as we may choose. It is a game that asks for our participation. It is a puzzle that we can propose a solution to without never really knowing whether our solution is correct.

This is the theory (or, part of the theory) presented by Lorenzo Scaretti's puzzles. They might serve as a new, desecratory, artistic syllabus or, at the same time, build a new ethic. And this seems a positive contribution to solutions to the human condition.

Toni Bonavita

1) ....in the "Lives of the Artists" Giorgio Vasari explains that a great artist does not accurately reproduce the world but draws forth images from himself.

![]()

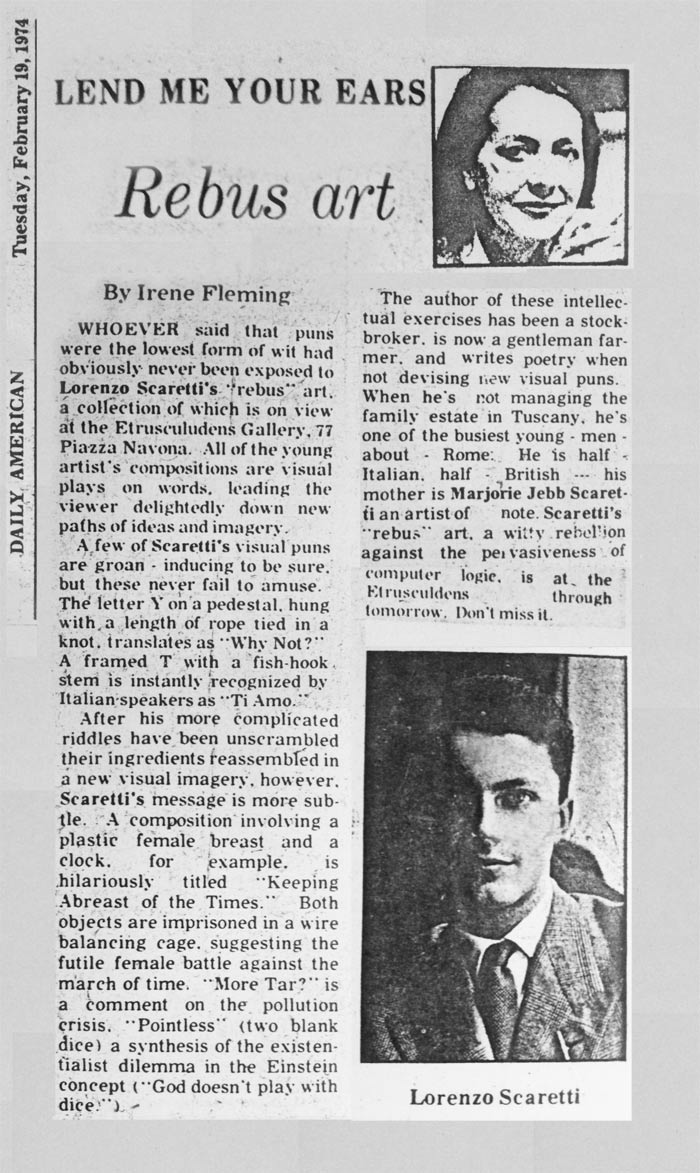

Rome - February 19 - 1974

LEND ME YOUR EARS - "Rebus Art"

WHOEVER said that puns were the lowest form of wit had obviously never been exposed to Lorenzo Scaretti's '"rebus" art, a collection of which is on view at the Etrusculudens Gallery. 77 Piazza Navona. All of the young artist's compositions are visual plays on words, leading the viewer delightedly down new paths of ideas and imagery. A few of Scaretti's visual puns are groan - inducing to be sure but these never fail to amuse. The letter Y on a pedestal, hung with a length of rope tied in a knot translates as Why Not? A framed T with a fish-hook stem is instantly 'recognized by Italian-speakers as "Ti Amo." After his more complicated riddles have been unscrambled their ingredients reassembled in a new visual imagery however, Scaretti's message is more sub-tle. A composition involving a plastic female breast and a clock, for example, is hilariously titled "Keeping Abreast of the Times". Both objects are imprisoned in a wire balancing cage suggesting the futile female battle against the march of time. "More Tar?" is a 'comment on the pollution crisis. "Pointless" (two blank dice) a synthesis of the existen-tialist dilemma in the Einstein concept ("God doesn't play with dice").

The author of these intellectual exercises has been a stock-broker, is now a gentleman farmer, and writes poetry when not devising new visual puns. When he's rot managing the family estate in Tuscany, he's one of the busiest young men about Rome: He is half Italian half British - his mother is Marjorie Jebb Scaretti an artist of note Scaretti's -"rebus" art, a witty rebellion against the pervasiveness of computer logic, is at the Eltrusculdens through tomorrow, don't miss it.

Irene Fleming

Rome - February 27 - 1974

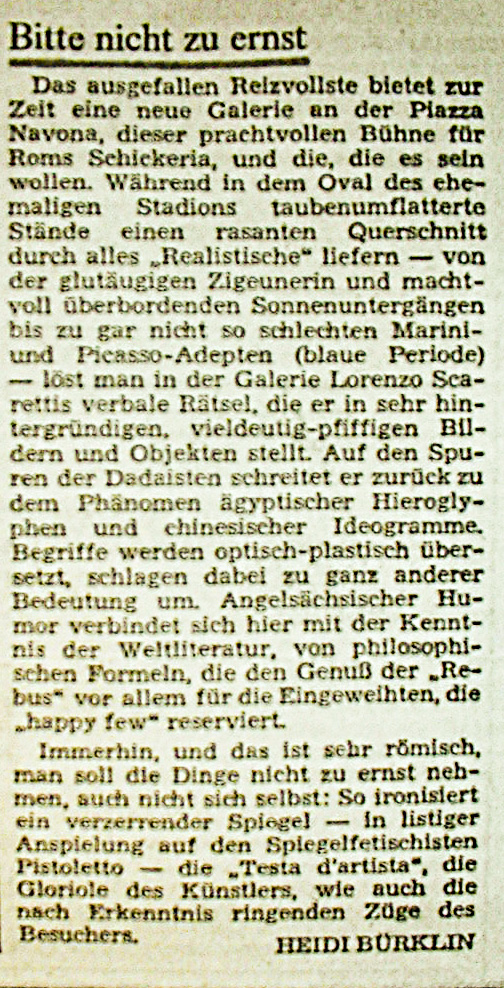

NOT TOO SERIOUS, PLEASE !

NOT TOO SERIOUS, PLEASE !

The most original (unusual) delight at the moment is a new gallery on Piazza Navona,the glorious stage for Rome's smart-set and those who'd like to be part of it.

While visiting this vast “oval” space, which was once a stadium, one encounters many little stands, surrounded by swarms of pigeons. Stands which offer a speedy cross section of all that is "realistic" in the art world, from glow-eyed Gipsy women and mighty over boarding sunsets to the not so bad Marini and Picasso adaptations (Blue Period). But suddenly here, at Lorenzo Scaretti’s new gallery show, one is challenged to solve verbal puzzles which this artist projects into very subtly cryptic and ambiguously clever images and objects. In the footsteps of the Dadaists Lorenzo journeys back to the phenomena of Egyptian hieroglyphs and Chinese ideograms. These concepts are translated visually and 3dimensionally into new meanings and sounds.

Anglo saxon humor interacts here with knowledge of world literature and philosophical considerations. This intoxicating mixture reserves the "enjoyment of the rebus and the pun" mostly for the “initiates”…the few, the “happy few”.

After all, this is very Roman, one shouldn't take things too seriously, especially not oneself.

So ironizes a distorting mirror…-alluding to the mirror fetishist Pistoletto-, the "Testa d'Artista", (the artist’s “Glory”), which witnesses and reflects the bemused and befuddled expressions of the visitors’ faces here struggling to comprehend.

HEIDI BÜRKLIN

1975

Elio Mercuri (art critic) - SENSE

Sense, in terms of the sense of a word or an image – which in fact is not sense - constitutes Lorenzo Scaretti's field of research. He works to discover true sense and true significance. This inevitably leads us to non-sense. Sense may signify meaning, but it may also signify banality, obviousness, emptiness and absence.

On viewing these works, we witness not only the repetition of the Dada school, de-consecration, mockery, and game through whose tricks life rediscovers its truth; but we get also the impression that there is an uneasiness to be redeemed and a solitude to be overcome.

The circle, the cube and the sphere are impalpable prisons which divide, making existence absurd, conversation impossible, contact illusory, meetings artificial; yet simultaneously they cause nostalgia to be true, dreams to be real and imagination tangible. It is a return to origins, where the word was object-thing-instrument for use, and not only a sound. The name was “numen” and not “omen”; a sign and not an absence.

Lorenzo Scaretti is insatiable in his quest for truth, simplicity, purity; an expectation of azure skies, limitless flights, vast space and perfect equilibrium. He seeks a spirit of clarity, a subtlety of intelligence and profundity of knowledge, so that everything can return to truth, like a flower that simply grows, and in so doing gives significance to the world.

Intelligence versus conformism, academic knowledge versus banality, poetry versus artifice. A back-to-front existence, contrary to every limit or wall, contrary to anything which might damage freedom, happiness or sensitivity. A struggle and a search that reveals an absolute anxiety to demystify and “de-define” everything that is warped by pretence, sham, illusion, deceit, mere appearance: the enemies of life.

The flight of a fly, the hand of a doll, a stuffed bird, the most abstruse of symbols, the most common of words used on a daily basis, return to what they really are; they no longer mean what we (by convention and habit or hypocrisy) say they should. In this way, opposites - the image and its double, the word and its sound - reveal true meaning, and we are able to experience the inherent truth of a sign, the significance of poetry, the purity of desire and the dream we have never forgotten.

These images reveal a direct contact with the continent of the unconscious, with unforeseen relationships in the territory of the infinite.

Intelligence can build - beyond the barriers erected by repression, violence, silence and fear - oases of innocence where life is life, love is love, words are words and images are images - and where we can find real freedom and happiness in the movement our lips make to produce a sound which is a w o r d .

Elio Mercuri

1977

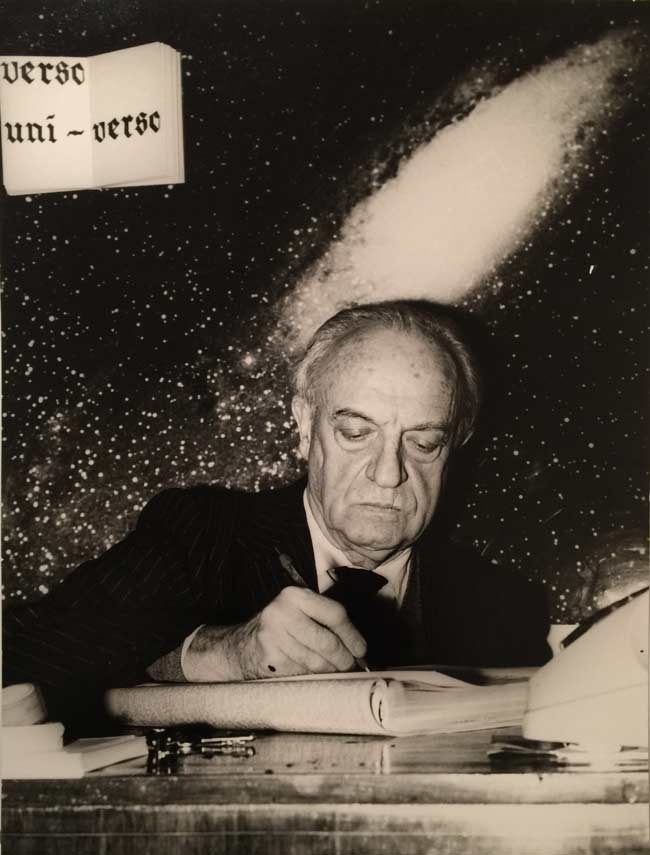

Ruggero Orlando (RAI- New York correspondent)

NEW PUN-IC WARS

Lorenzo Scaretti's artistic endeavours are an all-out "Pun-ic war" against the conventional.

If in art, as in strategy, the alternative to the conventional is only nuclear then the responsibility for the ultimate indecision will be left to those Hamlets of this world who reduce everything to dilemmas; dilemmas which in turn notoriously lead to tragic solutions.

It is an oriental tradition to let images rest on stilts made from words: in Chinese painting it is imperative to have descending rivulets of astonished verses to express the simplest of concepts; Arabs, condemned by the First Commandment to abstract painting, invented the arabesque: visual rythms of letters and verse.

In the west, however, a Giorgione who writes "col tempo" in the magical space under the portrait of an old woman is an exception – until of course Braque’s collages arrived or until the supremacist, or Jasper Johns, or "l’art pauvre" used the alphabet (since we are in a mood for citations) as Beethoven did in the last movement of the ninth symphony when Shiller’s words litterally blew from his creativity to complete the harmony of another means of artistic expression.

No. With Lorenzo Scaretti the word is in the beginning; whatever he may have learned from Magritte’s absurdly light blue skies or Fontana’s "teatrini" it is only a background in the same way as Renaissance pictorial sceneries are a background of the human figure: here these distinct artistic styles all subtly put to the use of other disquieting echos. It is of secondary importance that the comment to the phonetics is in two dimensions (painting) two and a half (bas-relief) or three (sculpture) nor should it come as a surprise when in subsequent developments Lorenzo Scaretti’s spatial dimensions will become four, five or even more.

Ruggero Orlando

1980

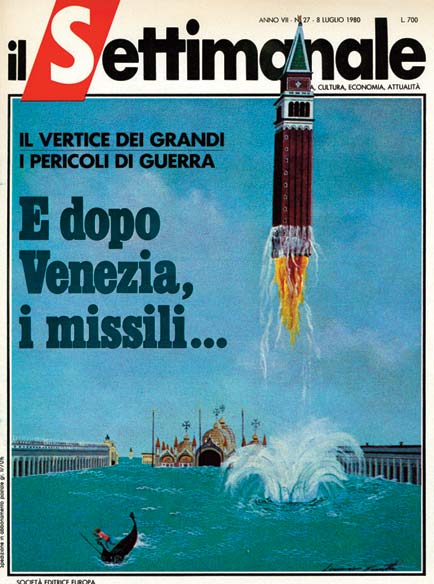

Italy -July 8 - 1980 "Mark One" (by Lorenzo Scaretti) cover of italian magazine: "Il Settimanale"

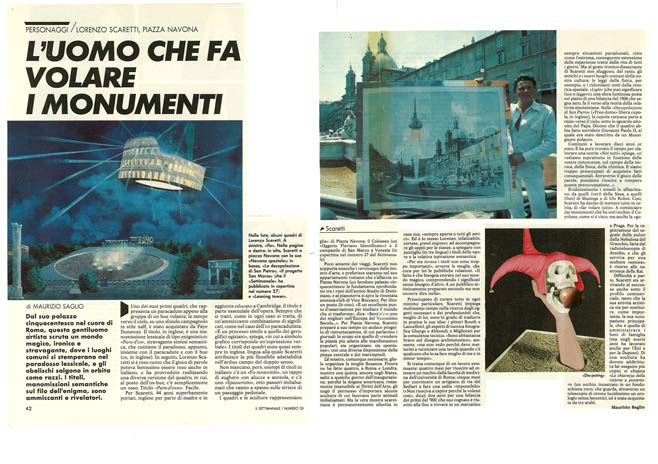

From inside the sixteenth century building in the heart of Rome, this gentleman artist gazes into a magical, ironic and extravagant world, where the common place is tempered in the lexical paradox, and obelisks rise into orbit like rockets. The titles, semantic manipulation of an enigmatic train of thought, are striking and revealing.

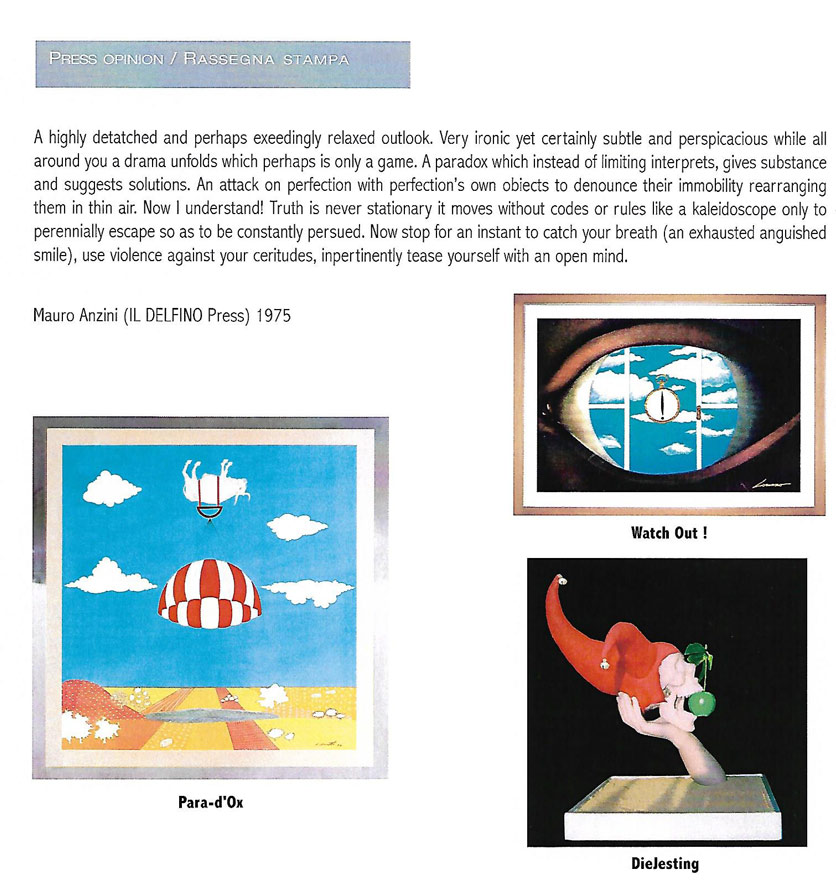

One of his first paintings, purchased by Faye Dunaway, pictures a parachute hanging from the back of an ox, its hooves reaching toward the sky, as it flies over a Naïf-style countryside. The title, in English, is an enigmatic lexical manipulation: " Para-d'ox", an extravagant semantic synthesis, which contains the paradox together with the parachute and the ox. Later, Lorenzo Scaretti realized that his play on words was achievable in Italian, as well, and he created another version of the painting, entitled "Para-d'osso, " in which, instead of the ox, he placed a simple bone.

It’s easy. For Scaretti, with his superbly carried 44 years, English on his mother’s side and educated at Cambridge, the title is an essential part of the artwork. Dealing, as always, with a daring combination of meanings, as in the case of the parachutist ox. "It is a process similar to that of Egyptian hieroglyphics," he explains, "where a graphic symbol corresponds to a verbal expression." The titles of his paintings are primarily in English, the language Scaretti attributes to having the most flexible adaptability to the elusive realm of the double sense. There are, however, many titles in Italian, too, such as "Fu-turacciolo" ( "What’s That ? That’s the Spirit!" in english), a painting of a winged and haloed wine cork, and another entitled "Spasserotto"

( "The GEight of Happy Sparrows" in english):, eight stuffed sparrows strolling on a pedestrian crossing. Squares and sculptures always represent paradoxical situations, seen as an extreme, consequential extension of everyday life experiences. However, the ancient and modern truisms of our culture, such as the laws of physics or repetitive themes of spatial rhetoric, have not been lost to Scaretti’s ironic and irreverent taste.

In "Light ?" (with its double sense of light as in illumination or light as in weight), a luminous sphere placed on a scale, dating from 1906, and weighing zero refers to Einstein’s theory of relativity.

In "La decupolazione di San Pietro," ("FreeDome" in english) the Vatican dome rockets into the sky under the dumbfounded gaze of the Pope. The story goes that the painting made even John Paul II smile as a Polish Monsignor described it to him. He started working ten years ago. Yet he even found time to elaborate on his theory: "All of us", he explains, "see ourselves primarily in light of our knowledge, in the fields of technology, physics and chemistry. We are too concerned about acquiring consequential facts. Through a play on words, we can break away from this concern..."

Evidently, rockets fascinate him: real ones from NASA and fake ones from Mazinga and UFO Robot. Thus, Scaretti decided to send everything into orbit and "make everything fly". He started with the monuments that were right under his nose: the large dome, which we have seen, but also the "spire" from Piazza Navona, the Colosseum ("IFO") and the bell tower of San Marco in Venice * (on the cover of issue 27 of the Settimanale).

He is not much of a traveler and Scaretti cannot bear art openings. He much prefers to stay in his apartment in Rome, overlooking Piazza Navona (a fabulous sixteenth century building: the foundation sunk deep into the earth touches on the remains of the ancient Domitian Stadium and the ground floor opens up to Vico Boccacci's renowned wine club. One might say the place is Di-vino (play on the Italian words for ‘divine’ and ‘wine’). "It’s an excellent observation point to study the changing world", he says. "Undoubtedly, one of the best in twentieth century Europe...". In his earlier days, Scaretti also prepared a daring restructuring project for Piazza Navona. The newspapers reported that the objective was to "make the piazza more suitable for both organized and impromptu local activities" by rearranging the central plateau and the sidewalks.

His wife, Susanna, arranges exhibitions, as necessitated. To date, he has done four of them in Rome and London, while a fifth, still ongoing in the States, skipped the inauguration by a few days since USA customs, crudely insensitive to the ‘Rights of Art,’ denied permission to import several sculptures that include parts of embalmed animals. However, the exhibit that best epitomizes the artist is permanently on display in his home and is "always open to all my friends." It is Lorenzo himself, tireless, courteous, the grand seigneur, who accompanies guests from room to room, tenaciously explaining the titles of works and their semantic inspiration (in three languages). "For me, the titles are not so important," his wife, who takes care of public relations, informs us. "The fact is that one has to enter into his magical world, understanding the meanings without needing much else. In my opinion, if the audience is artistically prepared, it isn’t necessary to say anything."

Worried about covering every detail, Scaretti takes a lot of time searching for the necessary objects and professionals, who are better able to translate his ideas into reality: painters Routh and Lancellotti, photography technicians Ghergo and Abbondi, and Migliorati for technical advice. "I'm pretty good at architectural design," he admits, "but I don’t see why I have to paint a board when there is someone who knows how to do it better than me and in less time." We are dealing, however, with a grueling job: four months to get a skull from the faculty of medicine at the University of Rome; five months to convince an artisan in via de’ Sediari to construct a chair. "Impossible." "He couldn’t understand why I wanted it the way I did," he says; two years for a scale from the early twentieth century, which his brother-in-law finally managed to find in a market in Prague.

For the recording of the Crab Nebula pulsar signal, made by the Arecibo radio telescope, and used for a "sound" sculpture,

("The Black Hole Truth") it was necessary to go to the RAI’s (Radiotelevisione italiana S.p.A.) audio archive. Difficulties aside, Scaretti is actually achieving commercial success, so much so that his artistic activity is gradually taking precedence over his main occupation, administration of the family assets (but in recent years he also worked For ENI -the Italian energy and gas company- and DuPont). For one sculpture, he actually had to produce more than one copy. Entitled "La chiarezza della visione a posteriori" ("Arse-tronomy" in english), it consists of an eye, embedded in a black colored derrière, looking through a shiny brass telescope at a clock without hands. The work of art was purchased by three Arabs.

Maurizio Saglio

1982

Peter Nichols, Rome correspondent for "the Times" of London, interviews Lorenzo in Rome.

Video published on You Tube under the title "Lorenzo and Peter Nichols" (35min)

"...Hello Lorenzo, what shocks do you have in store for us today...?!"

2016

Dr M E J Hughes - short literary comment

The title of this intriguing book by Lorenzo Scaretti sums up the paradox that he is investigating: visual phonetics. There is a sort of synaesthesia about his idea that sight has aural qualities and sounds elicit images. It didn't surprise me that in the interplay of senses he adds a tactile element as well, with sculptures (as well as numerous paintings with a sculptural quality). It says in the book that people are too often judged by their words and not enough by the images they produce in their minds: the book seems to aim to find some shared ground between the world of language and the world of thought.

The opening list of quotations offers another duality: compare Wittgenstein's idea that philosophy saves us from the attractions of language with Lorenzo's that language liberates us from the rational. Is language seductive and alluring, giving us permission to enjoy rather than to think; or does it allow us to escape out of the prison of thought? The answer separates the philosopher from the mystic.

The visual puns remind me a bit of the art-work of one of my favourite writers, Mervyn Peake. I am fascinated by puns and by the history of how punning is seen in relation to truth and reality. People have often seen puns as revealing of hidden truths rather than constructed, especially in the medieval and Renaissance periods. The best example of this is the mischievous false etymology for the title of the Bishop of Ely ( eliensis = of Ely) in a medieval satire on the merits of Norfolk: eli is said to mean Elijah (it is a standard medieval abbreviation) and ensis means sword, so eliensis gives us "the sword of Elijah"! There is a great essay by Felperin on Renaissance punning with the sub headings 'the pun made flesh' and 'the flesh made pun' -itself, of course, word-play!

I am very pleased to have had the chance of reading this beautifully-produced book, which -got me thinking- and which struck me as a very personal, individual account from someone who must have been thinking about all these matters for many years.